Advertisement

Sean Kirst: The ultimate World War I sacrifice transformed a Buffalo family

While the cloth bag once held a pattern, the green stripes are now faded almost beyond view. A few days ago, Michael Burns untied one knotted end, then shook out the contents on a table. They included some buttons, a needle and thread, a broken timepiece, an old razor.

Not quite a century ago, the U.S. War Department mailed the bag to Margaret Burns, wife of a shoemaker on Niagara Street in Buffalo. She had requested any belongings found with her son, James J. Burns, who died of his wounds in a military hospital in France on Nov. 2, 1918, nine days before the Armistice that formally ended World War I.

That was a century ago today.

"Even the smallest article," Margaret later wrote to the War Department, "will be appreciated by me."

She placed the cloth bag in a wooden trunk. It soon disappeared from family knowledge. Jimmy Burns, one of 10 brothers and sisters raised by their parents at 354 East St., gradually became a vague legend to his many nieces and nephews, and to their children.

It was not until a decade ago, when Jimmy's nephew Michael sorted through the contents from that old trunk in his Getzville home, that his descendants learned a truth about Jimmy's final gift that was compelling enough to change the way they see their own story.

“That’s the thread of life,” said Michael Burns, 70, a retired engineer whose late father, Donald Burns, was only 2 when Jimmy left for the war. "You never know how what you do is going to change things, and in what way, in the future."

Drafted in April 1918 at 22 from a job in a railroad yard, Jimmy served with Company K of the 310th Infantry. He was in Europe at the same time as a group of friends he called “the Black Rock Boys,” young men he would sometimes see along the front.

They included his next-door neighbor, Walter Gies, whose family lived only a few steps away from his own. Gies was written up as a hero in 1918 in the Buffalo papers, credited with saving several wounded men when their patrol was torn apart by snipers and machine gun fire.

He died in October 1918, only weeks before the fighting stopped. His name – like those of Jimmy Burns and many others – is engraved on a World War I monument in Riverside Park.

They were among more than 116,000 Americans killed by machine gunners, gas and other forms of slaughter in what was supposed to be “the war to end all wars,” a point recalled with grim whimsy by Michael Burns, a National Guard veteran.

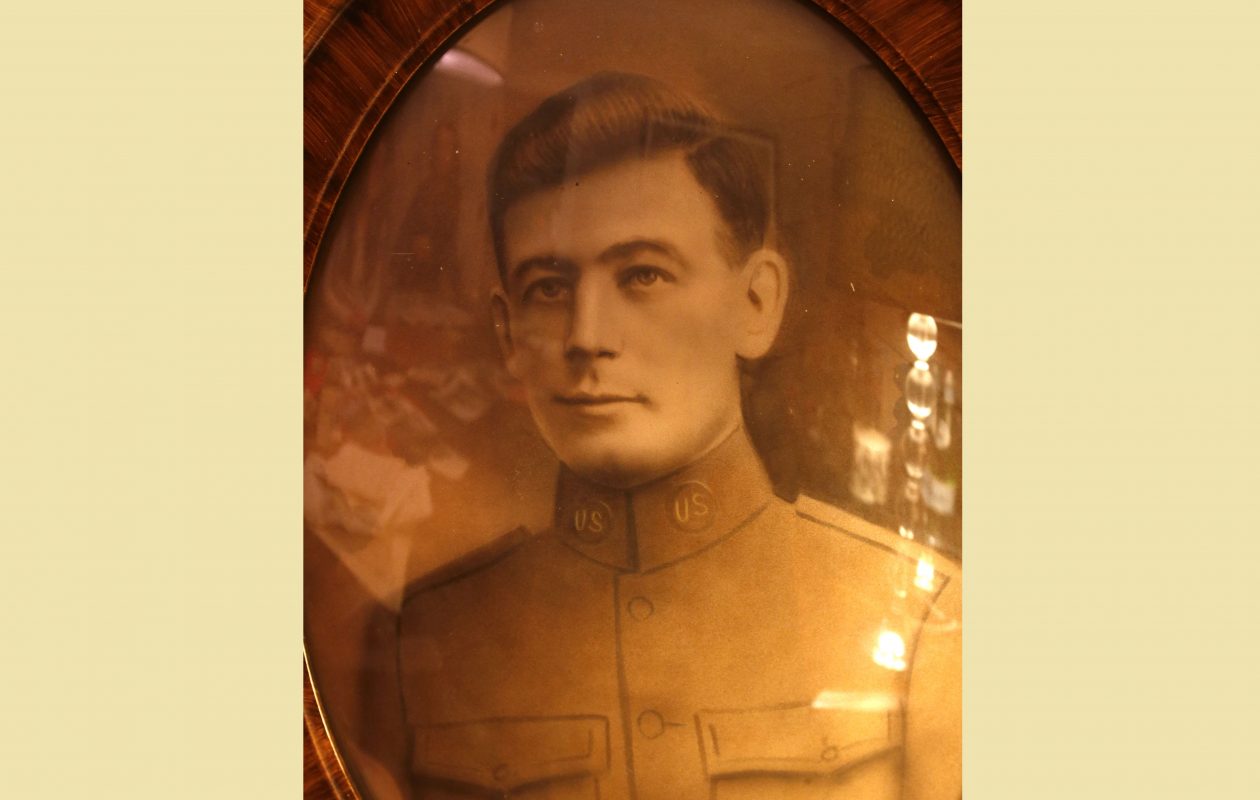

Michael Burns with his daughters Emily, left, and Hannah, right, a framed photograph of his Uncle Jimmy and a table covered with letters and mementoes related to Jimmy's service - and his death. (Robert Kirkham/The Buffalo News)

He is the guy who revived Jimmy’s story, thus helping his own adult children – Emily, Zachary and Hannah – to understand what it meant. Michael's father, Donald Burns, wound up with the wooden trunk that held artifacts carefully saved by Margaret Burns, mother to Jimmy, Donald and their eight siblings.

Those heirlooms - including a framed portrait of Jimmy in uniform - were passed down to Michael, and went into boxes in his Getzville basement. Maybe a decade ago, he finally sorted through the contents.

He found the old cloth bag, tied shut, with government documents explaining what it was.

Stunned, Michael began reading through a stack of Jimmy’s letters, which he brought this week to Emily's home in Buffalo.

Written in pencil, on lined paper, they began once Jimmy left Buffalo to go through training. His mood was thoughtful, even light, until he arrived at the front lines.

Everything changed. You can tell, said Michael Burns, that Jimmy suddenly realized there might be no way home.

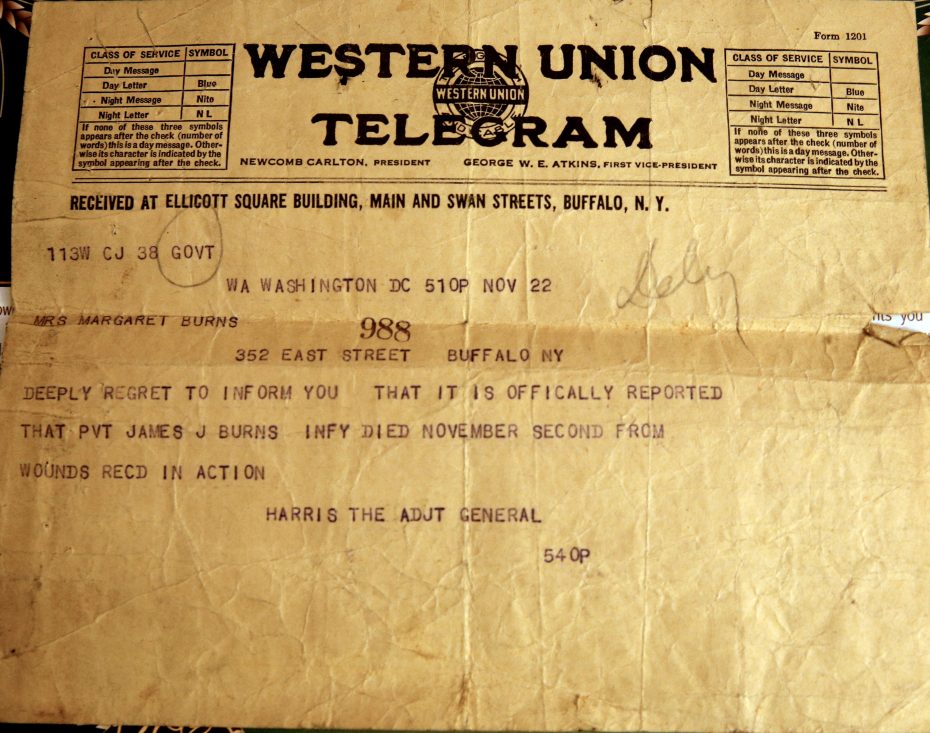

The War Department telegram informing Margaret Burns that her son Jimmy had been killed in World War I. The telegram arrived 11 days after the war ended. (Robert Kirkham/Buffalo News)

He was caught in the mechanized warfare that killed almost 10 million soldiers on both sides. In a letter written a week before he received his fatal wounds, Jimmy told his Irish-born father of his fear of “going over the top,” and his strange no-time-to-think-about-it calm once he found himself in the open, under fire.

In a separate letter to his worried mother, he promised to try and stay “in a state of grace,” and he made a vow:

“If I do get bumped off, I know that I will meet you again. If I don’t here, it will be in heaven.”

During this same period, Jimmy reminded Margaret Burns about an insurance policy he bought before the war from the Bureau of War Risk Insurance. Almost as a premonition, he urged his mother “to get after it.”

He died in a military hospital, according to a letter from his captain, after being caught in a mortar explosion. His parents learned of his death through a telegram that arrived 11 days after the war ended, when they were undoubtedly preparing for his return.

Jimmy was buried in an American cemetery at Meuse-Argonne. War Department auditors initially sent his mother and father his back pay, then wrote to say they had miscalculated. They demanded that a grieving family, surviving on the scanty income of a shoemaker, return $70 to the government.

Yet it was the insurance policy – money that Michael Burns had never heard about until he read the letters – that would have such impact on the trajectory of Jimmy’s descendants, including Michael and his children.

The policy paid $57 a month for 20 years. If that sounds like almost nothing, it was a life-changing amount for a poor working family, at the time. In 1935, for instance, going by a digital currency comparison, $57 was worth more than $1,000 today.

Michael said those payments allowed his grandparents to send three of their children to Canisius High School during the Great Depression. Donald Burns, Michael’s father, went on to Canisius College for a business degree that became the foundation of a career.

“It changes his life and probably my life,” said Michael, who earned an engineering degree at the University at Buffalo. He and his wife Nanette had three children, all college graduates.

The cloth bag sent back to Buffalo after the death of Private James Burns, along with other artifacts of his life at the home of his great-niece, Emily Burns Perryman. (Robert Kirkham/The Buffalo News)

Michael tries to see Armistice Day - now Veterans Day - as it was meant in the beginning, as a day to honor sacrifice and to dream of peace. Those intentions will leave him thinking of his Uncle Jimmy, who left school at 13 to take a job and help their family.

Among the documents, Michael found his uncle's teenage working papers. The child entered the full-time labor force after finishing eighth grade at the old St. Francis Xavier Academy, down the street from his house. He had blue eyes, stood 4-foot-10 and weighed 80 pounds.

From that point on, nothing in Jimmy's life was easy. His promise to someday reunite with his mother was realized in 1930, when the government provided passage to France so that Margaret Burns and other Gold Star mothers could finally visit the tombstones of their sons.

Margaret tucked away the handwritten note of condolence from Jimmy’s captain, a guy named Roy B. Thompson, who wrote after the war:

“The few men of the original company that are left will deeply regret his loss.”

For a while, Michael kept much of the story to himself. His children knew little about their great-uncle until Hannah came home one day from a fashion class at SUNY Buffalo State. She told her dad she had been asked to do a research project, to tell a story built around a quilt or any item of meaning, stitched from cloth.

Michael went looking for the simple cotton bag, ready for his kids to find their place within its fabric.

Sean Kirst is a columnist with The Buffalo News. Email him at skirst@buffnews.com or read more of his work in this archive.

Story topics: Armistice Day/ veterans day/ World War I

Share this article